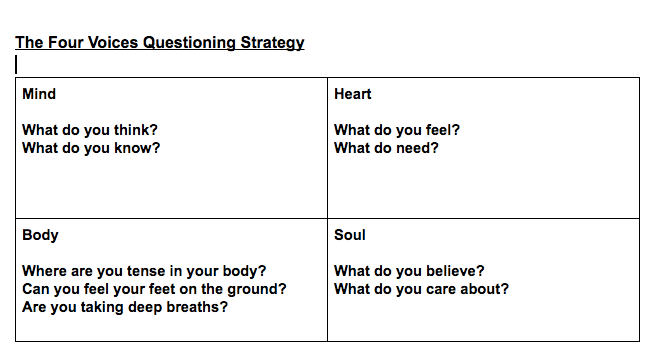

What do I need?

It’s a simple question, but I can’t help but wonder: have you ever asked yourself this question before?

What do you need?

It’s a simple question, but I can’t help but wonder: have you ever asked your students this question before?

Our lives are busy. Our classrooms are busy. There is so much to do and get done. Rarely do we pause in the middle of the day or the middle of a class, and ask:

What do I need?

What do you need?

We tell ourselves what to do constantly. Eat more kale. Get more sleep. Get off your phone during dinner. Fill out the field trip permission slip. Schedule the haircut. Mail gifts. Plan tomorrow’s lesson. Grade papers. Put gas in the car.

We tell our students what to do constantly. Listen to the directions. Write complete sentences. Finish your work. Stop talking to your classmate. Sit down. Sit still. Pay attention.

What if we stopped telling and started asking?

What if we started each day by asking ourselves, what do I need? What if we paused long enough that we listened to the answer?

What is we started each class by asking our students, what do you need? What if we paused long enough that we listened to their answers?

This is what I am thinking as I read Mirna Valerio’s post, An Open Letter To Women Who Aren’t Putting Their Needs First. Mirna is an athlete, a mom, a wife, a writer, and so much more. She writes about how it wasn’t until she had a major health crisis that she began to ask herself what she needed. She writes about how important it is for women to look after themselves just as much as they look after everyone else.

Why wasn’t I ever taught this? I think as I read. Why didn’t I ever teach my students this?

I believe that we have to teach ourselves how to identify our needs, listen to our needs, and act accordingly. This isn’t innate. In fact, many women (myself included) ignore that little voice inside their heads that says, “you need a break” or “you need to ask for some help.” We put on our metaphorical modern woman cape and charge on, determined to prove that we can do and be it all.

Until we can’t.

Because after all, we are only human and no one can multi-task her way through life without ever getting a cold or locking herself out of the house or losing someone she loves.

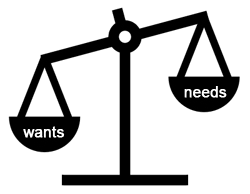

What do I want? We ask ourselves. What don’t I have? We think. What should I do? We ponder. Never, what do I need?

So what are modeling then for our students? For our own children? Do I want my son to think that he should continue working even when he has pneumonia? Do I want my students to think that finishing a worksheet determines whether or not they have learned something? No. Of course, not.

The other day as I was struggling to pack lunches, find hats and gloves and matching shoes, I got a glimpse of myself in the mirror. I looked feral, half-crazed, and exhausted. I was holding so many things in my arms that I dropped my mug of coffee and it spilled all over me, all over the stuff I was holding, and all over the floor. I started to cry.

My son said, “Mom. Do you need some help?”

My son asked me what I needed. He is six. All I could think about was what I wanted: more hours in the day, more sleep, more time to think. Paper towels.

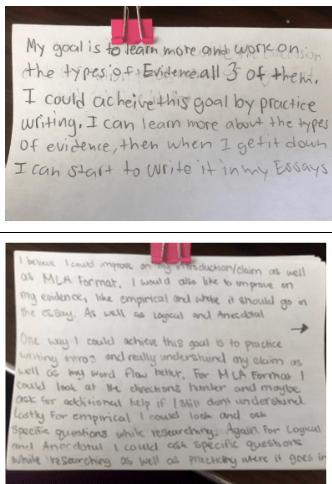

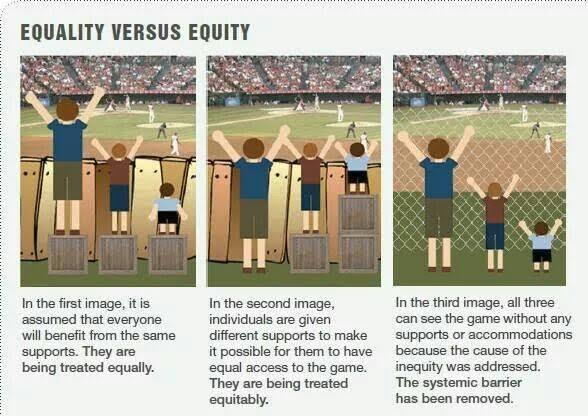

I am working with a teacher who isn’t new to the profession, but this is his first year teaching at a new school. He began the school year by setting expectations for his class, and telling his students what those expectations were.

When he came to our meeting, he shared that the students weren’t meeting the expectations and that they didn’t seem invested in them.

“If we create expectations for our students before they have walked into our classroom, how do we know that those are the right expectations?” I asked him.

“What if expectations are fluid, and constantly shifting as the students grow and the class progresses?” I proposed.

“What if we re-visit the expectations again and again and ask ourselves and our students what’s working and what no longer serves us?” I shared.

I challenged him to re-visit the expectations using a silent Graffiti Walk Protocol. In this strategy, the teacher writes questions on large pieces of chart paper. The students have seven minutes to walk around the room with a marker and write down their responses. Then the students re-visit the posters a second time, and they respond to their peers’ responses. They ask questions. They put a +1 if they agree. All of this (in theory) is done silently.

I suggested that the posters might provide entry points into a whole class discussion about what the students needed from the class and from their teacher to be successful.

In this strategy, expectation setting shifts from being a fixed teacher-driven process to a fluid student-centered process. Wants shift to needs.

After he tried the strategy, he shared with me that he felt much more connected to his students. The conversation flowed freely, and the students were eager to share and make suggestions about how to make the class work better.

He asked his students what they needed.

Another teacher that I am working with made a similar shift. Instead of telling her students what they were going to do, she started asking for their input. The class is working on a whole group essay. Part of the brainstorming process was to select three adjectives that describe the character at the beginning, middle, and end of the story. When the teacher saw that her students were having trouble distinguishing between adjectives and nouns, she shifted her lesson plan, and asked her students if they’d like her to slow down and go over adjectives and nouns with them.

She asked her students what they needed.

I challenge you to think about moments in your classroom where you could make the small shift from telling your students to asking them.

When a student is off task and disruptive, what would happen if you walked over to that student got down on her level, and asked, “what do you need right now?”

She may not know the answer, but by asking the question you have opened the door and you have shown her that her needs matter. At the end of the day, I believe all of us just want to be seen and heard.

As we round the corner into December, the season of goal setting, resolutions, and list making is upon us. I don’t think anyone is immune. Whether you plan to set a New Year’s Resolution or not, chances are you’ve seen something, read something or gone somewhere that planted the seed.

Like most women (and teachers, and well, let’s be honest, people in general), I have a tendency to set goals for myself that are big. I decide to change everything instead of something. My bucket list for the next year becomes long enough to fill a page. Family, Work, Finance, Fitness: I lean towards big shifts.

This year, I have been tiptoeing around my usual process because something has shifted in me. I don’t necessary want to accomplish more this year. I don’t want to run a marathon or plan all my meals on Sundays every week. I don’t want to teach my son how to spell by creating a Montessori inspired station rotation we complete every Saturday. Just thinking about these absolutes makes me want to take a nap.

This year I want to stop telling myself what to and start asking myself what I need. I hope to find more stillness, and in the quiet begin to listen to and honor the needs that surface, however big, however small, I hope to show up for myself, and have Mirna to thank for it.

Shift Small: Small Steps For Teachers And All Of Us To Start Shifting

1. Start A New Morning Ritual

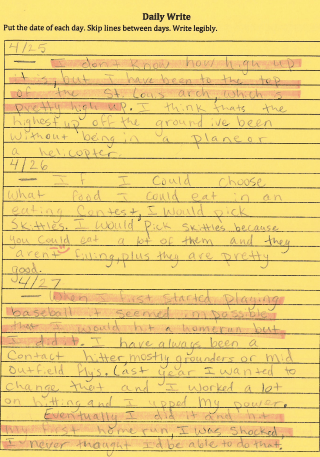

When you wake up what is the first thing you think of? For me, it is often, “I have so much to do,” or “I am exhausted already.” In order to shift my focus away from “shoulds” and “wants,” I am going to begin each day by asking myself what I need. Sometimes I need to cancel an appointment so I can take a nap. Sometimes I need to take a sick day when I don’t feel well. Sometimes I need to hit snooze. The problem is I feel like I am failing or doing something wrong when I really listen to what I need. Who am I disappointing? What am I failing at? I need to re-write my own story, and I challenge you to do the same. Our first thoughts set the tone for the day to come. Consider re-visiting how you begin your classes as well. Is there a small change that you could make so you can provide your students with time and space to think about what they need? Maybe instead of starting with a quiz, you can provide five minutes for them to journal or draw? Maybe you can start by asking them if there is anything they need to talk about before class begins?

2. Find An Accountability Partner

I feel very fortunate to have many women in my life who I admire. Several of these women are incredibly positive people whose joyful energy is contagious. Whenever I am around these women (Kelly, Afrika, Laura, and Anne I am talking about you!) I immediately find myself being more positive and finding more joy in whatever we are doing. It’s not easy to change your mindset and your thinking habits. Share what you are working on with your friends. Ask them to gently remind you when you begin to go back to old habits of negative thinking, doing too much and focusing on the “shoulds” and “wants.” It takes a village. Try the same process with your students. Consider pairing them up with a partner and supporting them to generate a list of needs, and then use that list to create some personal goals for themselves. By making time and space in the classroom for these conversations, you are showing your students that focusing on their needs is essential to their well-being. You are practicing what you preach.

3. Do Nothing

I know what you are thinking. What do you mean, do nothing? I can’t do nothing. I am not suggesting that you throw in the towel, curl up on the couch with the entire Harry Potter series, and call it a day. What I am suggesting is that you stop the rushing around, the multi-tasking. You don’t have to do everything in one day, and many days don’t go according to plan. The problem is we don’t seem ok with that when it happens. Your students will have days where they are distracted or tired or their braces hurt. That doesn’t mean you don’t teach, but that does mean you may need to pause, and ask what they need before you soilder on through your grammar mini-lesson. Sometimes the best thing that we can do for ourselves is nothing. We need to pause and create space before we can move forward.

(Running-Product)

(Running-Product)